Laura’s Inheritance, Laura’s Belly, and Descendants (exhibition, 2003)

Laura's Inheritance was an exhibition for which the artist imagined her two and a half year old daughter, Laura, as an adult woman. She paradoxically tackles the question of the future by invoking the materiality of the medium of printed photography, which she cuts and manipulates to become, indeed, future imaginings.

Uneasy with the pressure her daughter might feel in the future upon inheriting her mother's artwork/archive, as well as the pressure she might feel to have children herself, Cardelús imagined the three pieces of this show as a way to visualise, process, and ultimately do away with these anxieties.

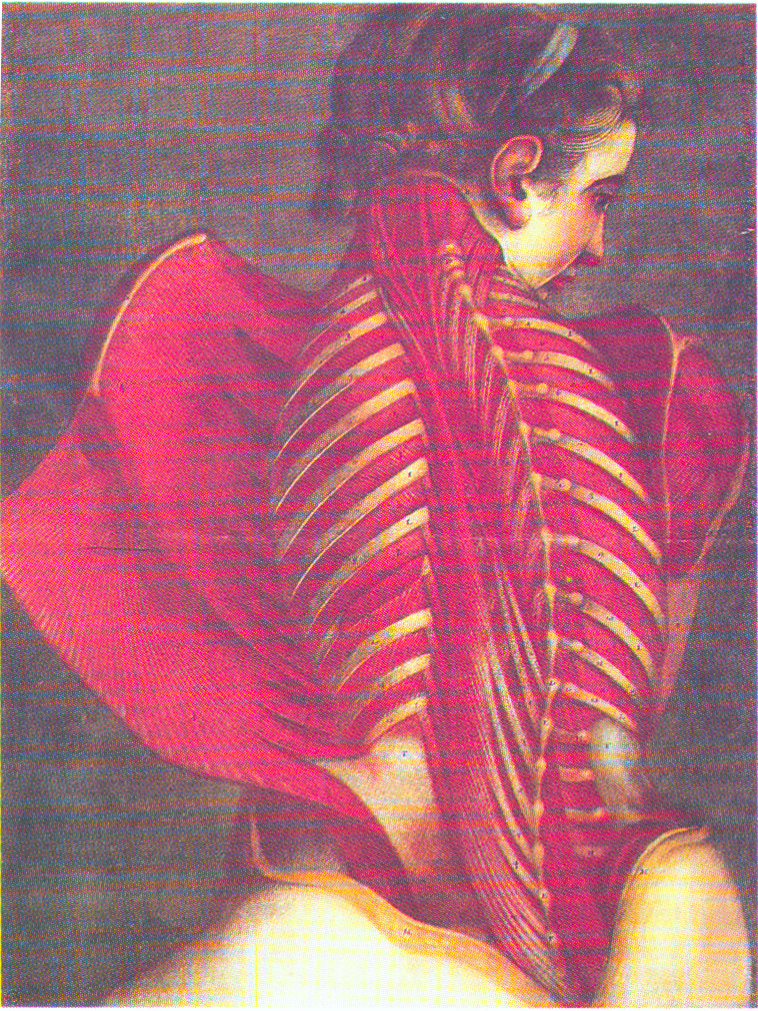

Laura's Inheritance, the largest of the works in the show, enlarges a photograph of her child to 4m, a giant meant to evoke the enormity of her daughter growing into adulthood. The giant child's stomach is cut open to hold dozens of enlargements of family snapshots cut into flower shapes, as though she were a vase. Cardelús felt that the flowers - representing her work and her future descendants - would, by virtue of the existence of this piece, be symbolically preserved and suffice to allay any pressure on her daughter. The c-section or écorché-like flayed stomach betrays, nonetheless, the inevitable pressure and conditioning - whether intentional or not - that all children feel from their parents.

Laura's Belly is a celebration of her daughter's toddler belly looking pregnant that imagines a future image that may never exist. The belly - a full moon, a ripe fruit - is encircled with cutout flowers made from family snapshots that invokes the tense and inextricable relationship between life and death.

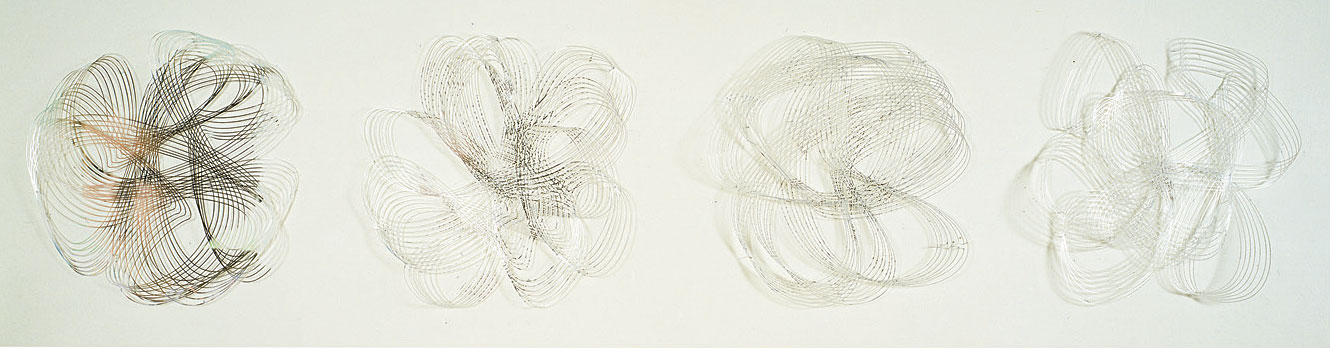

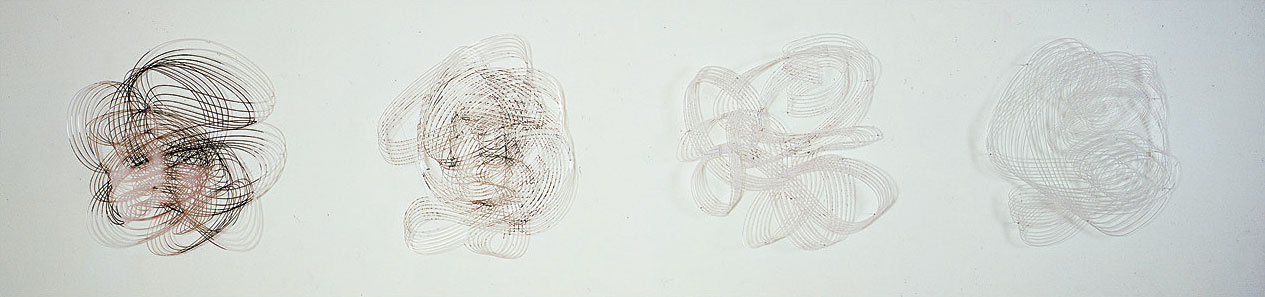

Descendants is a piece for which Cardelús imagines four portraits of four generations of descendants. The first portrait is a cutout of a photograph of her daughter. This first cutout portrait was then photographed, printed, and cut out to make the second portrait. She repeated this process for the third and fourth portraits so that with each new print, more and more of the figure is visibly lost to the cutting out process. Like genetic material, like memory, generation after generation, information is diluted and transformed.

2021

As a mother and artist working on family snapshots it was inevitable that one day I would be asking myself questions like : how will Laura (my daughter) feel about this when she is older? How do my children find their own way of seeing the past if I am always seeing it for them? How does one create a family’s story through images and at the same time leave freedom to the family members to act outside that myth? What will they make of a mother who spent hours in the studio working on them but not with them? My daughter Laura looks like me and was born on the same day I was. I photograph her and watch her grow. I exhibit her, and her brothers, to strangers who act like they know her. I hash over the past, pore over my grandmother’s collection of snapshots and my own archive for hours on end, then I spend days cutting them and turning them into something I claim is more ours than before. Where is Laura in all this? What will she do with the memories about remembrance that I am leaving her?

These questions were on my mind when I began working on Laura’s Inheritance at the end of 2002. I took a studio shot of three-year-old Laura (the one and only time I have “set up” a photo) and then blew it up to thirteen feet. I whitened her to make her look a bit less real, more porcelein-like. Imagining Laura as a woman made her larger than life, overwhelming. As a woman she became a vessel *, carrying inside of her a past to deal with. I made her into a vase by cutting her stomach open, and in it she holds a “bouquet” of memories—her inheritance. The flowers in her bouquet are blown-up, cut-out snapshots I picked out of my archive (many included flowers and some not) that I added gradually over the next five months. Like Ambrosius Boschaert’s Bouquet in a Niche (17th c), it pulls together an impossible bouquet from different moments in time, creating, as we do in our minds, temporary forms of meaning to hold together different experiences. While Boschaert seems to be saying “art transcends reality,” Laura’s Inheritance says “memory transcends reality.” Laura’s bouquet is both a violence (bursting out of her like an alien) and beautiful; both obscuring (she is partialy covered by the flowers) and enriching; a gift and a burden. Above all, a responsibility.

Naturally, Laura is me, too, reliving her own birth by cesarean section, and I am in her, wanting her to keep those flowers alive. Mother becomes daughter, and daughter becomes mother, only to repeat the cycle.

This piece is also about family snapshots, and falls into that long tradition of ordinary people trying to make up for what photography is and is not. A hundred years ago a mother may have embroidered a frame from a photograph of her daughter, or placed all the photos in an album to form some sort of narrative, or put one in a locket with a bit of hair. Today she might make a web-site, a photo-pillow, a picture-mug... I’m not much different from her. I bring the photograph closer to memory by eliminating a lot of the detail (giving as much importance to forgetting as to remembering), and investing it with a kind of material significance through time, labor, and the traces of that labor. At the same time the process slows down time and makes it possible to remember. But the snapshot is as mutable as memory, as hard to pin down as memory—both ocurr across a process, not at a single site—and while the snapshot frustrates a longing for that irretrievable past, it gives us a glimpse, albeit highly abstracted, of that past in excruciating detail. Hence the ongoing impulse to take a photo, and the ongoing impulse to look at it and save it and use it to reclaim something of the past, and finally, the impulse to resist its power.

*Blue Pearl and Descendents were two other pieces in the show Laura’s Inheritance: the first imagined Laura’s (my) pregnant stomach, and the other consisted of four portraits of her (my) imagined descendents.

Maggie Cardelús, 2003